Short answer, “No. Not yet.” Not according to this.

Two papers came out recently pitting human ears against computer analysis to see which is better at detecting musical similarity, and prompting headlines such as “Are computers really better at judging copyright infringement cases than humans?” and “Artificial Intelligence as a Solution to Unpredictable Musical Copyright Litigation.” The actual title of the paper I’m looking at today is more clinically titled, “Perceptual and Automated Estimates of Infringement in 40 Music Copyright Cases.” My interest was piqued despite, I read both, I have a few notes.

I jotted down my thoughts as I read the study.

We know the backdrop. Both of these papers address the idea that copyright infringement cases are far more frequent than they were five or six years ago, and that the way some of them go, there seem to be few objective means of adjudicating them. And therefore, “Hey could we get computers to do this more efficiently?”

The increase in cases is most often mapped to the “Blurred Lines” case five or six years ago (it wrapped up in 2018) in which Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams were found to have infringed upon Marvin Gaye’s “Got To Give It Up,” — a five million dollar judgment often said to have “opened the floodgates.” Also, there are implications stemming from the fact that this multi-million dollar verdict was wrong. (I don’t feel like equivocating today.) So, “Blurred Lines” likely opened the floodgates to mostly poorly justified lawsuits; lowering the bar and the barriers. And if it was indeed a wrong verdict with serious consequences, yes, why not hypothesize about a better, perhaps technology-aided method of evaluating these cases? Bring it on. It and I will get along fine.

There is also the fact that expert testimony is often less than ideally suited to help in court. The musicological testimony in “Blurred Lines” for instance was, in short, diametrically opposed, one expert said one thing and the other essentially disagreed and said the opposite. The jury had a short time to absorb, evaluate, and then ultimately believe one expert’s testimony or the other’s. Who to believe? Juries deserve our understanding.

If artificial intelligence learns to evaluate and identify infringement better than a forensic musicologist can, wouldn’t that fix some of the subjectivity, lead to better judgments, and discourage the least worthy cases from being pursued in the first place?

This study involved 51 human participants and a couple of software ones, and asked both groups to compare the musical works involved in 40 past and decided court cases, rate their similarities on a scale of one to five, and make the call, infringement or non-infringement. Those results were compared to the real-life results from those cases to see which set of participants, humans or machines, was better at predicting or arriving at the same judgment.

This study sought to improve upon earlier one from around the time of Blurred Lines in part by considering not just melody, but also non-melodic features such as lyrics and timbre. It tested the perception three ways; full audio recordings, midi performances of melodies only, and lyrics only.

My first note was that lyrics, when present, are certainly a musicologically important element. Timbre however is more of a performance element than a compositional one, and generally, less if at all protectable by copyright. By “timbre.” however, the study seems to mean “the audio of the full recording” as opposed to just the melody or the lyrics. The cases of Blurred Lines, Stairway To Heaven, and now what’s left of Thinking Out Loud, all show how badly plaintiffs want audio recordings played for juries. Recordings heard at trial can impact jury perceptions considerably. Another big ask, it’s difficult to listen and concentrate on protectable compositional elements but deemphasize or ignore unprotectable ones. Another example, when two songs are in the same key with the same orchestration lay listeners are bound to hear the underlying compositions as more similar; by definition, they sound more alike. And even as I’m considering this, I’m background thinking, “Good luck, algos. This stuff would be hard to model.”

First, why is likeness to the court decision the goal? Are the verdicts right by definition? If the algo or human disagrees with the Blurred Lines verdict, I say give them a point! Next, why are lyrics only versions playing such a large role here? Were the cases significantly about lyrical similarity? I’d assume, but it’s not clear. My Sweet Lord versus He’s So Fine certainly contained lyrics, but the lyrics have no similarity. What meaningful observation could come from a lyrics only comparison? In your melody only experiments, even after you presumably transpose both works to the same key, in the complete absence of harmony, I would argue your melody will have less diagnostic clarity and value.

And this paragraph gave me pause:

“Note that in the study we only considered cases in which substantial similarity of original expression played a major role in the decision, regardless of the outcome, but did not involve cases focused on

Yuan, Y., Cronin, C., Müllensiefen, D., Fujii, S., & Savage, P. E. (2023). Perceptual and automated estimates of infringement in 40 music copyright cases. Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval, 6(1), 117–134. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/tismir.151

sampling or the copyrightability of the contested musical expression in the complaining work (e.g., cases where two songs were similar but these similarities were shared with public domain works).”

There’s a name on this paper that I recognize (Cronin, C.), don’t know personally, regard highly, and assume to be the main selector of the cases in the study since his remarkable Music Copyright Infringement Resource page is the source of the cases. I may misunderstand something, but while excluding audio sampling cases makes obvious sense, it seems to me that it would be dicey to exclude on the basis of the copyrightability of the complaining work. Substantial similarity always involves some measure of banality weighed against absolute bulk gross similarity where one might be reliant on simply counting identical notes.

Spoiler alert: the study admits the presumption of correct case decisions is not ideal. More about that later.

The test for both groups was to listen to the songs in one of those forms (full audio, melody only, lyrics only), rate similarity on a scale of 1-5, and choose infringement or non-infringement. The test then asks how often the participant, human or algo, agreed with the court decision.

As for case selection, of the forty cases used, 22 decisions were no infringement and 18 were infringement. A positivity rate of 45% to me intuitively seems high and so again I’m questioning whether agreement with the verdict is a measure of anything useful.

A couple of quick takeaways in no particular order:

Both the algo and human groups actually matched past legal decisions best when they tested full audio. So much for too much data being confusing.

“My Sweet Lord” was interestingly the case where humans screw it up and rate the full audio versions as a 2 on a scale of 1-5. Whereas the algo comparing melodies found more than 50% identical notes and despite my concerns around harmonic context and the inclusion of rhythm, seem to have arrived at a decent result.

The human 51 participants matched and predicted the court decisions in 57.9%, 57.5%, and 51.5% across full audio, melody only, and lyrical only comparisons respectively. In other words full audio and melody only enabled them to match only 23/40 song decisions that matched the court, and lyrics were really a tossup.

On the algo side, they first explained melodic similarity, and described their process (Percent Melody Identity) as beginning by transposing the two works into the same key (great) and then eliminating rhythm by assigning equal time values (you’re kidding me) and then aligning (no, you’re just putting them in order) and counting the confluences.

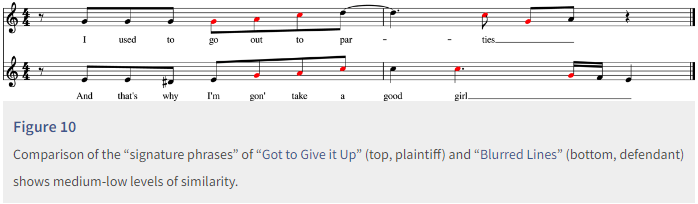

The case of “Got To Give It Up” and “Blurred Lines” is an example of why I’m not immediately taken with the melody-only tests. The study compares what they refer to as the “signature phrase” from the “Blurred Lines” analysis that won the day and remark that it’s only 45% similar to the one in “GTGIU” and thus comparable to “chance from two random melodies composed from the same scales,” and I’m confused, interpreting this as “any two melodies, twelve notes long, taken from the same scale are likely to be about half the same,” which is nonsense except for a very narrow definition of “same.”

The figure below is taken from the study.

This is a familiar pair of lines to lots of people. “I used to go out to par-ties” is how “Got to Give It Up” begins, and “And that’s why I’m gon’ take a good girl” is the lead into the chorus of Blurred Lines, probably the song of the summer ten years ago. And while the algo, laypersons and I can all count notes that share the same pitches, I would assert that the musical contexts of these melodies are completely different, arguably opposites, which gives them different musical meaning and value even at the note by note level. In other words, identical pitches can be considered less identical when the context is different. “Got To Give It Up” opens with this line and the accompanying harmony is “tonic” which is to say it is establishing the starting point, home base, functionally stable and comfortable. The compared line from Blurred Lines is accompanied by the “dominant” which is the arguably opposite, least stable, and inclined to change to the tonic and find stability again. In “Blurred Lines” it’s all a build up to the chorus which arguably begins on “good girl!” more akin to when a drummer plays a drum fill as a transition and build up to the next thing. The upshot is that melodic differences are bound to be underappreciated in

the absence of their defining contexts.

Perhaps these sorts of things contribute materially to their finding, contrary to their predictions, that reviewing full audio versions led to better predictions than melody-only or lyrics-only versions. The full audio data is so much richer that it makes up for its faults.

The paper is concerned with and tries to correct for participants bias toward non-infringement. I wonder what I’m missing here. Were the participants told the case results were nearly 50-50? I wonder because to me they likely didn’t err nearly enough. This is my bias if you like, but I’ll explain. The notion that an infringement case is a toss-up when the case starts, if that’s their assumption, is wrong, and in my opinion distorts jury trials. By the time a case has survived motions to dismiss and goes to trial, many good and bad arguments have been considered, but the threshold for dismissal is not 51-49%. Judges can be thoughtfully reticent to dismiss, and we’ve seen cases that survived to be brought before juries, that after a finding of no infringement, see the defendant awarded legal costs. In such cases, it is reasonable to at least ask if the court might’ve ruled itself and saved everyone’s time. It certainly acknowledges that the trial is not a toss-up by virtue of making it to a jury.

In the end, the study acknowledged that since the “relative emphasis on melody, lyrics, and other music aspects… changed from case to case” we can only expect so much from any one objective method of measuring similarity. It also acknowledged the compromised reliance on past cases as “ground truth.” Give ’em a break. It’s hard to find a better ground-truth sample. The MCIR is a terrific website that catalogs most of the more interesting and important music copyright cases from the past century or so. But another assumption the study appears to accept, that these listed cases, by virtue of their having reached judgment, not settled out of court prior, are representative of the 50-50’s where both sides are assumed to have better reasoned arguments than dismissed or dropped cases assumed to be more one-sided and unworthy of the financial risk of one of the parties. This ignores numerous factors, I think, but I’m sympathetic.

The humans won 83% to 75% in terms of correctly predicting the court decision; not what you might expect from reading the headlines and links referencing this study. For now, when the algo used it’s melody counting process, it behaved similarly to humans who heard full audio and melody only but differed widely compared to those humans who looked at lyrics only. And the process more akin to a computer ‘listening’ to the audio did much more poorly. This is research; much came before, much will follow. Right now the results support the idea that while software may be able to supplement human analysis, it won’t replace it. Now I find myself the less skeptical one.

I suspect the tools will catch up, and perhaps not that long from now.

Here’s the study:

Yuan, Y., Cronin, C., Müllensiefen, D., Fujii, S., & Savage, P. E. (2023). Perceptual and automated estimates of infringement in 40 music

copyright cases. Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval, 6(1), 117–134. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/

tismir.151

And it can be found on the website of The International Society for Music Information Retrieval’s Journal