This could get interesting. In fact, I think it might be the first of its kind. Give me a little rope.

In a recently filed lawsuit, the estate of Barry White claims that “Everlasting Bass,” released in 1986, infringes Barry White’s 1973 song “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby.” Awwww yeeah, Baby. And before we get into it, let’s recontextualize the well-reported idea that Kendrick Lamar, Future, and Metro Boomin aren’t the target of this lawsuit. They may not be the defendants, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t targeted.

“Everlasting Bass” is a classic example of 1980s West Coast hip-hop by Rodney-O & Joe Cooley, a duo known for pioneering the West Coast electro-hop sound. It was a staple in clubs and radio stations, especially among fans of bass-heavy music popular in Southern California at the time. The driving rhythms, catchy hooks, and bass lines (obviously) have been sampled and referenced by several artists over the years; most recently and probably most significantly “Everlasting Bass” is the sample behind “Like That” by Future, Metro Boomin, and Kendrick Lamar (yes, the one with the Drake diss).

“Like that” is how kids the age of my kids know the “Everlasting Bass” groove, which is understandable. “Everlasting Bass” was never a huge hit song, even though it kinda puts Rodney-O and Joe Cooley in the hip-hop pantheon. Evidently, “Like That” woke up someone from the estate of Barry White, who waited decades to sue, and that’s understandable as well. There wasn’t all that much to gain and the statute of limitations on Everlasting Bass struck midnight long ago. But the “Like That” clock has barely struck 5AM by my calculations, a long day ahead, and “Like That” which contains “Everlasting Bass” is making beaucoup bucks.

Everlasting Bass came out in the late eighties, when Barry White was still living, and it’s appeared in lots of other songs, so what took so long? The White estate evidently says they have waited forty years to sue Everlasting Bass because it was “released prior to the internet and was not widely distributed.” They were “unaware of the song when it was first released.”

“I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby,” was a top ten hit from White’s 1973 debut album “I’ve Got So Much To Give,” and they have a point; one prominent bassline in “Everlasting Bass” indeed sounds a lot like one in “I’ve Got So Much To Give.”

It’s amazing, considering how many times I’d imagine “Everlasting Bass” has been sampled and cleared, that this hasn’t come up before. Perhaps everyone assumes Rodney-O and Joe Cooley cleared “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby?” And it’s also curious that this lawsuit skips over Future, Metro Boomin, and Kendrick Lamar, for the time being, and sues Rodney-O and Joe Cooley for the original offense. “Like That” was a number-one hit, so perhaps that’s what it took to get their attention, or for them to say “enough is enough,” but they’re not suing “Like That.” They’re going back to the source.

How much do they sound alike? Well, a lot. A slam dunk lawsuit for Barry White’s estate? Nah. Not even close actually. This could take some interesting turns.

First, here’s what we’re talking about: “Like That,” “Everlasting Bass,” and “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby.”

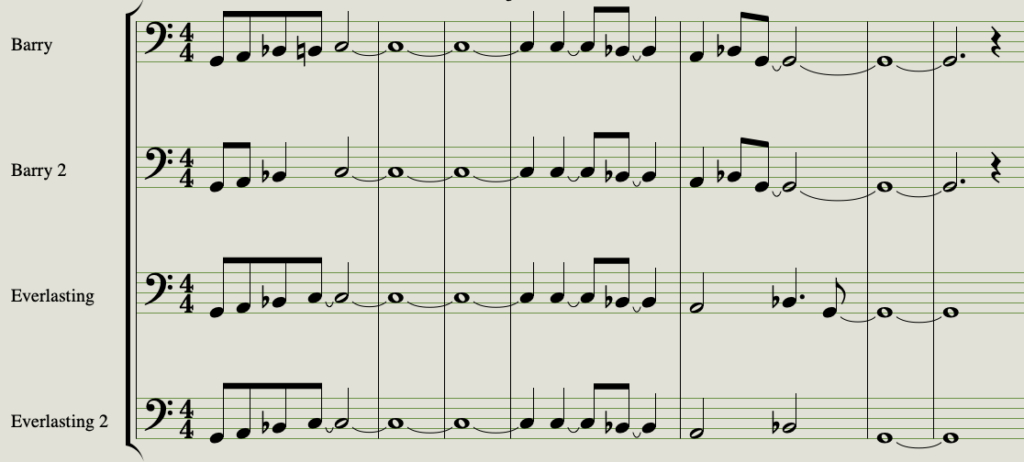

Side by side, this lawsuit is about these ten seconds of “I’m Gonna Love You Just A Little More Baby” and ten seconds of “Everlasting Bass.”

I haven’t even read the complaint yet, but it can’t expand much beyond this: the first few bars of Barry White and the first few bars of Everlasting Bass are very much the same. When you listened side by said, you could hear that they’re in different keys, but if I transpose them into an apples-to-apples common key for you, even if you don’t read music, you can probably see that they’re as alike as they sound.

Both songs play their ascending then descending melody twice, and here I labeled the second ones “2.” In other words, Barry plays the top line, then the second. Everlasting Bass plays the third followed by the fourth and you can see where they line up and where they don’t.

But similarity on its own isn’t enough to win a lawsuit. A finding of infringement is based upon the copying of original and protectable material, and enough of it that we should care. In other words there are similarities about which we might not care.

I’d argue this is one of those times. It sounds crass put this way but WHO EVEN CARES? Maybe we do. Let’s keep going.

These phrases are brief, just nine notes in total, four notes up, five notes back down, followed by a repeat of the whole thing. The pitch series in the two works is essentially the same, and the placements and durations of the notes are mostly the same. They’re not identical, however. The very first measure from “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby” contains a note not found in “Everlasting Bass;” they are different from the very start. One gets to its target note in four notes and the other takes five.

It’s not as though this is an especially distinctive pitch series. For one thing, just off the top of my head, these could be the first five pitches of James Taylor’s “Your Smiling Face.” And pay attention to the term I used: “target.” These bass parts begin on G and want to arrive at C, the target. In so brief and simple a musical idea and goal, there are a limited number of ways to fill the space between. It doesn’t even do it the same way every time. That’s how much it doesn’t matter. Moreover, we’ll never hear this part again after the first thirty seconds of Barry’s seven-minute track. It’s a mostly unrelated little intro before the real song starts, the sort of thing that might’ve gotten thrown together in the studio like the Beatles’ intro to Eight Days A Week.

This is also little more than a four-note scale up and down. Setting aside that B-natural note in Barry’s first measure which doesn’t appear in “Barry 2” or the “Barry 3″ that I skipped over because it’s just a half repeat of Barry 2” or anywhere at all in Everlasting Bass, the G A Bb C is just the first four notes of a G minor scale. If I were following the conventions around abstraction, filtration, and comparison that sprung from Judge Learned Hand I might be asked, “What if we filtered out the elements from these basslines that are unprotectable, and then looked only at what remains?” I could easily make the case that nearly every note is part of an ascending or descending minor scale, is not protectable and therefore in the eyes of copyright, arguably irrelevant. Generally speaking, I’m not the biggest fan of that sort of filtering. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t a useful exercise.

Consider also, that these phrases sound more important and more alike partly because of their context. In both works, this element is featured in relative isolation. A musical phrase such as these, G up to C along scale tones, would go unnoticed as a bass line in the context of a fuller orchestration. A bass player at a bar on a Friday evening could play those figures all day long in any song that goes from G minor up to either C or C minor and back; it would be a simple, common, non-event. In these two productions though, just drums and bass, it sounds much more like “Everlasting Bass” is quoting “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby.”

Now we’re getting somewhere. Remember I asked “Who Even Cares?” Well, sometimes we don’t. Sometimes it’s not worth it. Society wants more music, art, and literature. Copyright seeks to promote creativity through the incentives around protecting and rewarding intellectual property rightsholders, but it’s a balance. Creativity can be influenced by prior art, and we allow a certain amount of that, and even borrowing.

Most of the time, I discourage “fair use” as a defense because I reject the idea of “use” at all, fair or otherwise, when substantial similarity is to me obviously not in evidence. But I also have to concern myself with what a finder of fact, arbiter, judge, or jury, will be able to understand clearly. Sometimes, I have to begin with, “Now I know this looks bad, but…” and then explain why they should believe me and not their lying eyes, or ears. If my client is wrongly accused, I’d rather things don’t look bad in the first place. Here, I’d admit this doesn’t look great.

Could they have created that bass line without having heard “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby?” Sure. It’s not sampled. It’s just a very similar bassline. And that reasoning is far reaching. It’s a simple part that just ties together two of the most obvious chords in any given song written in a minor key, which feeds into both the argument that it could’ve come about by coincidence, and the argument that it’s too brief, simple, and common to be original to or protectable by Barry White.

But on the other hand, is it going to be seen as probative of copying that these two songs have essentially the same bass lines, and both appear in the introductions to the respective works, played on keyboards mostly set against only a drum or drum machine part? Yeah, it don’t look great.

But if it is taken from Barry White, “fair use” might be exonerating. Fair use is determined by looking at the following four factors.

I’d say all four favor the defendant here.

The purpose and character of the use is different in that Barry never sings a lyric nor plays any other instrument or voice along with that bass line which only appears in the first 7% of “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby.” Arguably the whole song is a commentary on the importance of a catchy bass riff in a hip hop track. One thing is for sure, it’s not a typical Barry White message.

As for the Nature of the copyrighted work, well, I might argue that musical elements so brief, basic and common as this are tantamount to facts rather than creations. Their placement and use is creative. The element itself is selected as much or more than created.

The amount and substantiality of the portion used is multi-faceted. Again, this disparate bass part appears in the first 7% of the track and never again, and the work is wholy unbeholden to it. It’s minimally significant. It barely matters to the Barry White track as a composition. It’s worth is a function of the fact that “I’m Gonna Love You Just A Little More Baby” was a hit like “A Hard Day’s Night.” (look it up)

Does “Everlasting Bass” affect the potential market for “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby?” On the contrary.

Has there ever been a decision in a non-parody music copyright case where the fair use doctrine was the principal defense? I don’t think so.

Edward Lee, a professor at Santa Clara University and one of the best-known experts in intellectual property, conducted experiments and wrote a paper exploring why fair use isn’t more often the defense of choice given its apparent efficacy. I’m going to go re-read that paper asap. But I’ve given my reason for avoidance already. It’s that I’m loathe to even concede “use” where I don’t see it, even though it might be the most practical and high-percentage strategy.

As a musicologist and not a lawyer, that’s ordinarily more someone else’s call. Here though, I can really see it. And the more I consider it, the more it’s becoming a prediction. The first non-parody fair use case in music copyright is upon us.

1 Comment

Great read! You should check out the current status of the lawsuit. You may find it very interesting