Do you remember when Disney got sued because “Let It Go” sounded like “Volar?” No? Me neither, but here we go again.

Earlier this week, Daniel E. Grigson, filed a complaint in a Los Angeles court, claiming that “Some Things Never Change” from Disney’s Frozen 2 infringes upon his song “That Girl,” which he wrote and published under his own label about 20 years ago. Grigson claims that he heard the similarity while attending the movie back in 2019 and “… involuntarily stood straight up, turned to look at his wife, and then at his kids, his eyes wide open as saucers. The close similarity to his own work “That Girl” was so striking to him that it caught him off guard, the beat, rhythm, feel, theme, words. He sat back down with his head in his hands. His 11-year-old daughter leaned over to him and said, “Dad, Disney took your song.”

Yes, that whole outing-ruining scene is spelled out in the actual complaint — a little dramatic, perhaps, but honestly, my first response is sympathy. It’s a lousy feeling when you think you’ve been taken advantage of. And if his daughter really did say that, I hope she was beaming with pride at the idea and not upset by it. I’m a Dad. But, the 11-year-old is wrong. Similar? Sure. Stolen? Probably not.

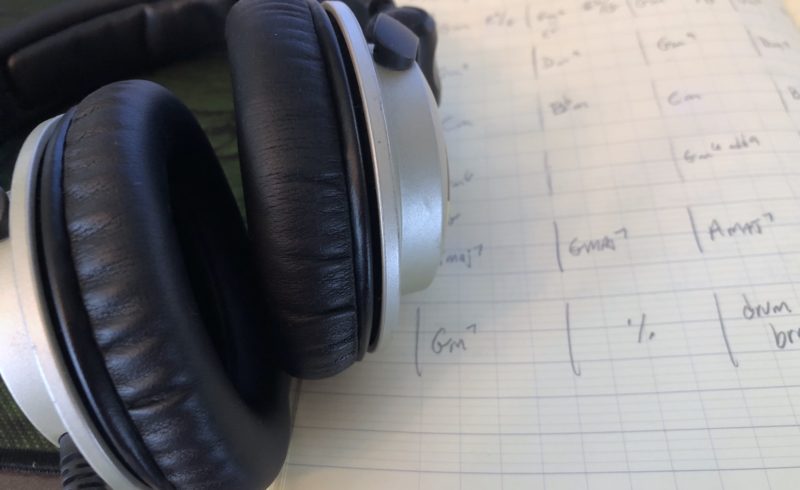

Here are the two songs if you’d care to try to hear what Mr. Grigson hears:

The plaintiff evidently went back and took a good look at the two works and then consulted a musicologist who seems to have validated his concerns. So, here we are.

The musicologist should’ve talked Grigson down. And I can’t say it’s going to be terribly interesting for you to read why, but that’s what we do around here.

Fortunately for us, the complaint is pretty detailed, claiming similarity in “melodies and melodic structure; musical forms and musical gestures; rhythm sections parts; tempos; chord progressions; cadences at the end of the choruses; lyrics; and arrangements and lyrical structures.”

For starters, are the tempos of both songs “identical” and 92 BPM (beats per minute) as the complaint says?

Nope, they are neither. We’re off to a rip-roaring start. I have to ask, why would one not anticipate scrutiny and try to uphold a standard?

Identical? Which would you have everyone believe, that you are disingenuous or incompetent?

Not that it matters a whole lot, but “Some Things Never Change” has a tempo of 90 BPM, and “That Girl” kinda drifts around between 91-94 or so. I would say “That Girl” is mostly 92 BPM or so, and a “drifting 92 or so” isn’t all that different from a BPM of 90. But no, they’re not “identical.”

And anyone who ever rode in a backseat and watched other cars’ wheels spin in and out of sync would find it awfully hard to fathom the substantiating claim, “Comparing corresponding clips from the two songs compiled by GRIGSON, the tempo and rhythm are so similar they kept time and rhythm without alterations.”

I know that when I put these two songs up at the same time, their time and rhythm drift unpleasantly out of sync in just a couple of seconds.

As to “similar forms,” song form in popular music centers around familiar terms like intros, verses, chorus, and bridges. And indeed, these two songs do present their sections in the same order. They both begin with an intro, then they sing a verse, then a chorus, then another verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, and they wrap it up with an “outro” section (that’s a wordplay, the opposite of “intro”) Using common shorthand now, these are both “ABABCB” forms, where A is the verse, B is the chorus, and C is the bridge. The thing is, “ABABCB” might be the most common form there is. So this observation is valid, but not especially significant. Tempo, key center matter hardly at all. Form, not a whole lot more, especially in this case. They’re all probative of copying, just usually not very.

The complaint looks at harmonic similarity next, and there’s more weirdness right away as they explain their first musicological process, that “Some Things Never Change” was “transposed from C Major to G Major,” to match the key of G major that “That Girl” is performed in. This transposition into a common key is standard methodology. It makes the comparisons easier and helps the musicologist to show and explain the findings to others. But “Some Things Never Change” is not in C major to start with; it’s in F major. It happens to modulate up to G major in its last minute or so, but regardless, it’s never in C major. So it’s also nonsensical to claim that Grigson transposed “That Girl” down “2 steps” to match the keys for his own analysis since transposing two steps down would actually put his “That Girl” into the not-helpful key of Eb major.

Disconcerting? Yes. But these are cheap “gotchas,” and they don’t make the harmony any more or less similar. Lets say both works are in the key of G, and get to something that does matter at least a bit, the chord progressions. Chord progressions are famously not usually protectable because there are only so many to go around and that’s true, but harmony gives context and meaning to melody, so harmony matters a lot.

So what about the claim that the respective four-chord progressions in the first four bars of these choruses are “very similar” even while the second of the four chords are not identical; Em in one case, and Am in the other?

The chords in the chorus to That Girl are (although it varies a little across the several choruses in the song):

|| G Em | C D | G Em | C ||

(Those vertical lines are bar lines; they occur every four beats.”

And “Some Things Never Change” is:

|| G Am9 | C D | G Am9 | C D | Em C | G C/E Bb Bb/D | D7sus ||

Short version? The progression is That Girl is beyond common. Even if it were the same in both songs, which it isn’t, it’s Heart and Soul — the thing every third grader can jump on a piano and rattle off.

The long version? If you look at the first six or seven chords, you can see what they’re saying. But this is only about nine seconds of music, a fairly brief and not identical progression. And I’d argue that those A minors and E minors are the chords that give these two very common progressions most of what modest character they possess. Often, two different chord progressions might contain two chords that are different in name, as here, but relatively similar in harmonic function. And here, the complaint tries to argue they exhibit similar harmonic movement and background for their melodies, but I disagree. I think those two different chords have a lot of impact and are quite different sounding.

They are as different, for example, as the progressions in “All I Have To Do Is Dream, ” and “Love Is All Around.” These are the same two progressions as our two songs, respectfully, and yes, Love Is All Around is the song from “Love Actually.”

These progressions are very common, especially the one in That Girl. I mentioned “Heart and Soul” but it’s also the main progression in Stay, most familiar to me as the thing Jackson Browne sings after LoadOut, but actually by Maurice Williams; Please Mr Postman, Stand By Me, This Magic Moment, we could go on and on.

Importantly, this only sorta similar material makes up only half of the chorus to “Some Things Never Change.” The rest will be completely dissimilar. And before we leave this topic, the very next claim is that in ‘That Girl’ the “final chord in the phrase appears as C/D and sometimes D,” while in the Frozen song, “it is D7sus.” And “although the chords are different, they are both variations on a D chord and serve the function of a “5 Chord.”

Remember that they mentioned this, the “cadences at the end of the choruses” in that list of supposed similarity.

But, no. The chord in “That Girl” actually appears as C, and sometimes as A minor, but never as either of the chords they claim and additionally these chords function, not as a “V” chord similar to the one in “Frozen,” but as a “IV” chord, which is its own thing. So apart from their both having a long-held cliffhanger chord before the chorus wraps up, which is a very common device, the cadences are different. Also, it’s the same device the defendants themselves used in “Do You Want To Build A Snowman” when Anna sings “I wish you would tell me WHY.” So, they’re doing something they do. They didn’t get it from your song.

Before we entertain the ideas expressed around similarities in the melody or at least melodic arc, can we touch upon the lyrics? “Some Things Never Change” by itself is not an original lyric. A quick search on Lyrics.com tells me it will appear in 183 other lyrics. And “Some People Never Change,” has 12 matches of its own. These two phrases are actually colloquially different, opposites in some ways! “Some Things Never Change” is used here to be assuring, whereas “Some People Never Change” is more of a resigned condemnation.

Melodically, the complaint focuses on those same two bars that contain those somewhat similar but very common chords, and sees those two lyrical phrases and points out eight similarities, four in the first bar, four in the second. I’ll write them out when I have a sec. See if you can follow this for now:

The very most basic means of comparing melodies is what you would expect. I look for identical pitches appearing at the same times (rhythmic placement) and held for the same duration. And then, for a copying argument to be strong, I look for conspicuous strings unlikely to have occurred by coincidence.

Here, syllable by syllable, “Some” is the same pitch, but is different in duration and rhythmic placement. Next, whether we’re singing “Things” or either syllable of “People” we’re on different pitches. Ne-ver are never on the same pitch but are rhythmically the same in both placement and duration. And “Change” is a different note as well, but occurs at the same rhythmic placement and for a different duration.

ONE note is the same. One, in the key phrase.

Two in total for the entire two-measure example. “That Girl” in these two measures contains seventeen notes. Two, the same.

I’ve never met a musicologist I didn’t like, but this next bit would set me on a bad path:

While there aren’t any notes to speak of that are the same, they depict the last four notes of “Some Things Never Change” as an “inversion” of the last four in “That Girl.” What’s an inversion, you don’t ask because you rightly don’t care? “Melodic inversion” is a compositional technique where you take a melody that for example starts on C, moves UP a diatonic step to D, then down three diatonic steps to A, and then, because you’ve perhaps been taught in your 20th century composition class at conservatory that inversion is cool, you write a sort of reverse of that, beginning perhaps but not necessarily again on C, then instead of up, you write the next note DOWN a diatonic step to B, and then UP three diatonic steps to E. You’re writing melodies that move by the same intervals as before, in the opposite direction as before. Is this musicologicially significant or probative of copying? Sure, sometimes. If I found a melody a dozen notes long and then another melody in the next measure or a corresponding measure that was a perfect retrograde inversion of those twelve notes? I’d surmise the composer employed that technique.

So they’d have us believe Lopez and Anderson-Lopez derived their melody by taking the four notes from “That Girl,” which are B down one to A, down one to G, down three to D, and inverting them, G up one to A, then up one to B, then up not three but two to D, because I dunno, they couldn’t count to three?

What it actually is, simply, is “Mi – Re – Do – Sol” versus “Do – Re – Mi -Sol.”

When we hear “Do Re Mi” do we ask, “how on earth did you come up with that?” No.

Do those sound at all the same? No.

Have we indulged this long enough? Yes.

There are a few pages of observations left in the complaint, but that last one wore my patience. Inversion is a thing. It’s all over the place in classical music. In Jazz, you’re taught to do it when you’re learning to stretch material. In serial music, it’s rudimentary. But is it the best explanation of how one song goes DO RE MI and another goes MI RE DO? No.

A musicologists job is to illuminate the musical matters for the finders of truth to consider. This is more like confusing them and getting them to focus on a shiny meaningless sideshow.

Ed Sheeran is right when he says there are too many cases like this out there. That’s not Mr. Grigson’s fault, nor his burden, and he’s entitled to his opinion. And I remain sympathetic, truly. He owes it to himself and to his eleven year old to make sure he has not been taken advantage of.

A musicologist and the courts should assure him he has not been, and he should go back to living his, I hope, happy and fulfilling life, not haunted by any of this. Probably too late for that.

1 Comment